Dr. Jameel Hadji, PhD

Abstract

The Anthropocene, widely regarded as a new geological epoch, marks a period in which human activity has become the dominant force shaping Earth’s systems. Unlike previous eras in which environmental changes occurred primarily through natural processes, the Anthropocene foregrounds the profound and pervasive impact of human action on the climate, hydrological cycles, biodiversity, and planetary geochemistry. Among these anthropogenic effects, climate change stands out as the most immediate and consequential challenge, threatening both natural ecosystems and human societies worldwide. Rising global temperatures, intensified weather events, sea-level rise, and shifts in ecological patterns constitute urgent, cross-border challenges that traditional governance frameworks struggle to address. The scale and complexity of these threats demand a reconsideration of global governance and international diplomatic practices, particularly in the realm of climate negotiation.

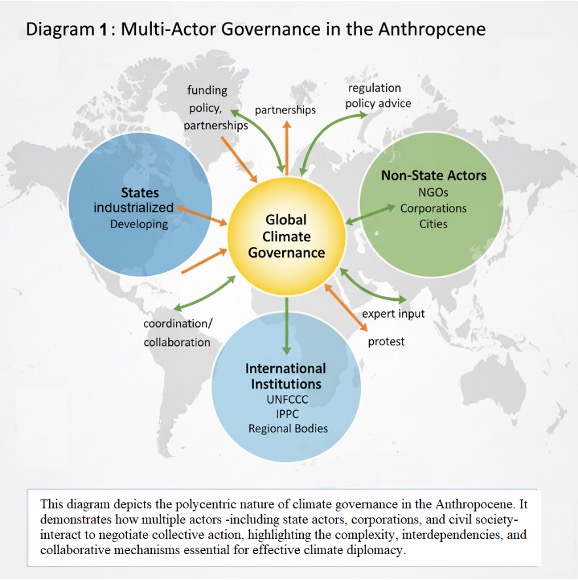

In the Anthropocene, climate change is not merely an environmental concern or an economic challenge; it is an existential political issue that tests the mechanisms of international cooperation. The interdependence of states, transnational institutions, non-governmental organizations, and private actors creates a highly complex governance landscape. States must balance competing objectives—economic growth, domestic political legitimacy, national security, and global reputation—while vulnerable nations face disproportionate climate impacts, raising critical questions of justice, equity, and historical responsibility. Consequently, climate diplomacy emerges as a crucial arena in which survival, fairness, and collective action are negotiated simultaneously, bridging the divide between scientific urgency and political feasibility.

This dissertation examines the evolution of climate diplomacy from the Rio Earth Summit (1992) to the Kyoto Protocol (1997), the Copenhagen Accord (2009), and the Paris Agreement (2015). These milestones illustrate the iterative nature of international negotiation, revealing both the potential and limitations of global diplomatic mechanisms. The Paris Agreement, for example, introduced a flexible “pledge and review” framework to encourage broad participation, yet it also exposed the fragility of voluntary commitments and the continuing influence of power asymmetries among states. Through these case studies, this research highlights the interplay between scientific knowledge, diplomatic negotiation, and political feasibility, showing how global governance structures have adapted—or failed to adapt—to the challenges of climate change in the Anthropocene.

The dissertation further investigates the role of non-state actors in climate governance. Cities, corporations, advocacy networks, and civil society organizations increasingly participate in governance processes traditionally reserved for states. Examples include the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, corporate sustainability initiatives, and transnational climate finance mechanisms. These actors contribute to polycentric governance, enabling innovation and experimentation in climate policy. However, such decentralization also introduces challenges, including coordination difficulties, fragmented accountability, and inequities in influence and resources. Understanding the contributions and limitations of non-state actors is therefore essential for assessing the effectiveness of contemporary climate diplomacy.

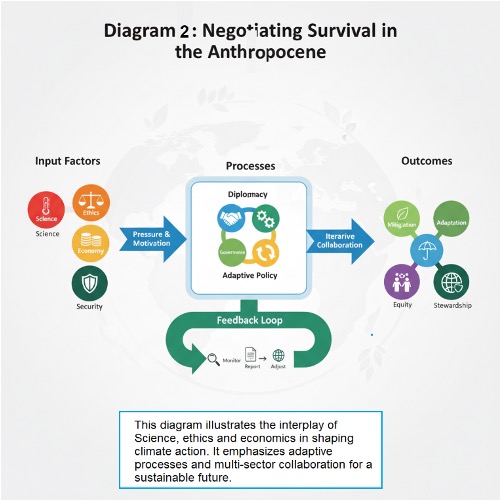

Central to this study is the argument that the Anthropocene necessitates a paradigm shift in diplomatic practice. Traditional diplomacy, focused on short-term national advantage, economic interests, or military security, is inadequate in addressing threats that are systemic, global, and existential. Climate diplomacy in this context can be understood as “survival diplomacy,” where negotiations extend beyond national interests to encompass the long-term viability of human civilization and planetary systems. Effective governance requires continuous negotiation, trust-building, adaptive policy design, and mechanisms that integrate scientific knowledge with ethical responsibility.

This research contributes to the fields of international relations, environmental politics, and global governance by providing a comprehensive analysis of climate diplomacy under the conditions of the Anthropocene. By synthesizing historical developments, theoretical perspectives, and contemporary case studies, the dissertation demonstrates that survival in a human-dominated epoch depends on the capacity of states and non-state actors to engage in cooperative, forward-looking, and justice-oriented diplomacy. Ultimately, the study underscores that achieving meaningful global action requires reconciling political feasibility with ethical imperatives, scientific guidance, and the collective responsibility of humanity to safeguard planetary survival.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Climate Change and the Anthropocene: A Global Challenge

Climate change has emerged as the defining diplomatic and governance challenge of the 21st century. Unlike traditional security threats, which are often geographically or politically bounded, climate change transcends national borders and affects every region of the globe. From rising sea levels in the Pacific islands to intensifying droughts in Sub-Saharan Africa, from extreme heatwaves in Europe to unprecedented storms in the Americas and Asia, the impacts of climate change are both widespread and increasingly severe. These environmental transformations are closely interconnected with social, economic, and political systems, making them multidimensional and highly complex. As a result, climate change is no longer solely an environmental or economic concern; it is an existential issue that demands coordinated global action.

The concept of the Anthropocene further underscores the urgency of this challenge. In this epoch, human activity has become the dominant geological force, altering the Earth’s climate, hydrological cycles, biodiversity, and biogeochemical systems. Industrialization, urban expansion, deforestation, and the emission of greenhouse gases have caused changes at a planetary scale, leaving limited space for incremental solutions. The Anthropocene signals a critical shift in human responsibility: humanity must confront the consequences of its transformative influence and act decisively to safeguard the planet. This perspective emphasizes that environmental governance cannot rely solely on localized or short-term strategies but must instead address systemic, global, and long-term risks that affect both current and future generations.

1.2 Climate Diplomacy and the Evolving Landscape of Global Governance

In response to these unprecedented challenges, climate diplomacy has emerged as a central mechanism for managing global climate risks. Climate diplomacy encompasses negotiation, policy coordination, and the creation of institutional frameworks that bring together actors with divergent priorities, capabilities, and interests. States must navigate a complex terrain of competing objectives, balancing economic growth, national security, domestic political pressures, and global obligations. Meanwhile, vulnerable nations face disproportionate exposure to climate impacts, highlighting issues of equity, justice, and historical responsibility. Instruments such as the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR) reflect these concerns, recognizing that while all nations share the obligation to combat climate change, their respective contributions and capacities differ significantly.

The evolution of international climate agreements over the past three decades provides valuable insight into the challenges and opportunities of climate diplomacy. The Rio Earth Summit of 1992 laid the foundation for global environmental cooperation, while the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 established legally binding emission reduction targets. The Copenhagen Accord of 2009 highlighted the difficulties of achieving consensus among states with divergent interests, and the Paris Agreement of 2015 introduced a flexible pledge-and-review framework designed to enhance participation and inclusivity. While these agreements demonstrate progress, they also reveal persistent challenges, including limited compliance mechanisms, insufficient ambition, and the influence of power asymmetries among states.

Beyond state-led diplomacy, non-state actors have assumed an increasingly important role in global climate governance. Cities, multinational corporations, advocacy networks, and civil society organizations have implemented innovative climate initiatives, from urban sustainability projects to transnational carbon finance schemes. These actors contribute to polycentric governance, characterized by overlapping jurisdictions, adaptive policymaking, and experimental approaches to problem-solving. However, decentralized governance also presents challenges in coordination, accountability, and equitable participation, underscoring the need for integrative strategies that connect multiple levels of action.

Ultimately, climate diplomacy in the Anthropocene represents a form of survival diplomacy, in which negotiations extend beyond traditional national interests to encompass the long-term viability of human civilization and planetary ecosystems. This dissertation explores how international climate agreements, non-state actors, and governance mechanisms interact to address global climate threats. By analyzing the politics of justice, inequality, and cooperation in this context, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how climate diplomacy can evolve to meet the existential challenges of the Anthropocene.

Chapter 2: The Evolution of Climate Diplomacy

Climate diplomacy has undergone significant transformation over the past several decades, evolving from a peripheral environmental concern to a central element of international relations. The trajectory reflects both the growing scientific recognition of climate change and the political complexities inherent in achieving global cooperation. At its core, climate diplomacy seeks to reconcile the imperatives of collective action with the sovereignty and interests of individual states. This chapter examines the historical development of climate diplomacy, highlighting major milestones, institutional frameworks, and the ongoing tensions that shape international negotiations.

2.1 Early Environmental Diplomacy and the Rio Earth Summit

The origins of climate diplomacy can be traced to broader environmental initiatives in the 1970s and 1980s, including the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (1972) and the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 1988). These early efforts emphasized the scientific and ethical dimensions of environmental stewardship, laying the groundwork for coordinated global action.

A landmark moment in the evolution of climate diplomacy was the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, which produced the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC established a legally binding framework for international climate cooperation, recognizing the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR). This principle acknowledged that while all states share responsibility for addressing climate change, developed countries bear greater historical responsibility and possess greater capacity to lead mitigation efforts. The Rio Summit highlighted the interplay between scientific consensus, ethical responsibility, and state sovereignty, setting the stage for future negotiations.

2.2 The Kyoto Protocol: Binding Targets and Emerging Challenges

Building on the UNFCCC framework, the Kyoto Protocol (1997) introduced legally binding emission reduction targets for industrialized countries. This represented a significant step in operationalizing climate diplomacy, as it moved from declaratory principles to concrete obligations. The Protocol also established mechanisms such as emissions trading, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and Joint Implementation (JI), which sought to provide flexibility while achieving emission reductions efficiently.

However, the Kyoto Protocol faced severe limitations. The United States, a major emitter, refused ratification, citing concerns over economic competitiveness and equity. Developing countries, not subject to binding targets, expressed skepticism over the fairness of obligations placed solely on industrialized states. These challenges revealed a fundamental tension in climate diplomacy: the need for collective action versus the political and economic imperatives of individual states. Despite its shortcomings, the Kyoto Protocol established important precedents in monitoring, reporting, and compliance that would inform later agreements.

2.3 The Copenhagen Summit and Lessons in Consensus-Building

The Copenhagen Climate Change Conference (2009) was intended to produce a successor framework to the Kyoto Protocol. However, it exposed the limits of consensus-based diplomacy. Negotiations were hampered by divergent priorities among industrialized and developing countries, disputes over financing, and disagreements on mitigation commitments. The summit concluded with the Copenhagen Accord, which recognized the urgency of climate action but relied largely on voluntary pledges rather than binding obligations.

Copenhagen highlighted several lessons for climate diplomacy:

- Sovereignty and domestic politics significantly influence negotiation outcomes.

- Equity and finance remain central issues, particularly for developing countries vulnerable to climate impacts.

- Flexible, inclusive mechanisms may be more politically feasible than rigid, top-down mandates, even if they risk lower ambition.

These lessons would directly shape the approach adopted in subsequent negotiations leading to the Paris Agreement.

2.4 The Paris Agreement: Inclusivity and Voluntary Commitments

The 2015 Paris Agreement represented a pragmatic breakthrough in climate diplomacy. Unlike Kyoto, it embraced a “pledge and review” system, requiring states to submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) while allowing flexibility to reflect national circumstances. This bottom-up approach prioritized inclusivity and near-universal participation, creating a framework capable of adapting to changing political and scientific conditions.

The Paris framework also institutionalized mechanisms for transparency, reporting, and a global stocktake every five years, designed to encourage incremental increases in ambition. Importantly, it recognized the role of non-state actors, including cities, corporations, and civil society, in contributing to mitigation and adaptation efforts. The evolution from Rio to Paris illustrates a trajectory in which climate diplomacy has gradually shifted from top-down, binding commitments toward adaptive, polycentric governance, balancing the tension between collective action and state sovereignty.

Chapter 3: Global Governance and Its Limitations

Global climate governance has emerged as a central concern in addressing the multifaceted challenges of climate change. The scale, complexity, and transboundary nature of climate impacts necessitate coordinated responses among states, international organizations, and non-state actors. Despite the establishment of formal governance structures, global climate governance remains fragmented and polycentric, reflecting the interplay of competing interests, institutional limitations, and evolving power dynamics. This chapter examines the architecture of climate governance, its institutional limitations, and the challenges posed by a fragmented, multi-actor landscape.

3.1 Institutional Frameworks and the Role of the UNFCCC

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) serves as the principal institutional framework for global climate governance. Established at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the UNFCCC created a platform for states to negotiate commitments, share information, and coordinate strategies to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Over the past three decades, it has facilitated the development of landmark agreements, including the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Paris Agreement (2015), which have structured global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote sustainable development.

However, the UNFCCC faces significant constraints that limit its effectiveness. Its consensus-based decision-making process often leads to lowest-common-denominator outcomes, as states with divergent interests must agree before formal adoption of policies. Additionally, enforcement mechanisms under the UNFCCC are weak, relying primarily on voluntary reporting and peer pressure rather than binding sanctions. This structural limitation undermines the capacity of the UNFCCC to ensure compliance and maintain ambition among states. Furthermore, disparities in economic development and historical emissions between industrialized and developing countries complicate negotiations, often generating conflict over equity, responsibility, and financial support. These limitations highlight the inherent tension in global governance: balancing inclusivity and legitimacy with decisiveness and effectiveness.

3.2 Polycentric Governance and Fragmentation

Beyond the UNFCCC, climate governance has evolved into a polycentric system, characterized by multiple, overlapping centers of decision-making across local, national, regional, and transnational levels. Cities, corporations, non-governmental organizations, and regional bodies now play increasingly significant roles in climate action. Networks such as the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability, and corporate sustainability initiatives exemplify decentralized approaches to mitigation and adaptation. These actors often pursue innovative policies and experimental strategies that can accelerate climate action beyond the capacities of national governments.

While polycentric governance demonstrates adaptability and innovation, it also introduces challenges. The multiplicity of actors and overlapping initiatives can create confusion, duplication of effort, and inconsistent outcomes. Coordination among different levels of governance is often weak, resulting in gaps in accountability and enforcement. For example, city-led emission reduction programs may be ambitious but lack integration with national policies, limiting their overall impact on global emission targets. Similarly, corporate initiatives may prioritize reputational gains over systemic sustainability, raising questions about legitimacy and fairness. The fragmented nature of polycentric governance illustrates both the potential and the limits of multi-actor approaches in achieving coherent, equitable, and effective climate solutions.

3.3 Challenges of Accountability, Legitimacy, and Effectiveness

Fragmentation in global climate governance raises critical questions about accountability, legitimacy, and effectiveness. Accountability concerns arise when actors operate independently of formal oversight mechanisms, making it difficult to ensure compliance with agreed-upon standards or commitments. For instance, voluntary pledges under the Paris Agreement rely on self-reporting, leaving room for underperformance without formal consequences. Similarly, decentralized governance initiatives by cities or corporations are often monitored by third-party certification schemes, which may vary in rigor and reliability.

Legitimacy is another key challenge. Global governance structures must maintain the confidence of both states and citizens to be effective. When governance is dominated by powerful states or elite actors, less influential nations or marginalized communities may feel excluded from decision-making, undermining the perceived fairness of policies. This tension is particularly evident in North–South dynamics, where developing countries demand recognition of historical responsibility and access to climate finance, while industrialized countries emphasize voluntary cooperation and flexibility.

Effectiveness in climate governance depends not only on coordination and compliance but also on the ability to translate policy into tangible environmental outcomes. Despite decades of negotiations and the proliferation of governance experiments, global emissions continue to rise, indicating persistent gaps between diplomatic commitments and real-world implementation. Achieving effectiveness requires integrating scientific knowledge, adaptive policymaking, and robust monitoring systems while ensuring that governance structures remain inclusive, accountable, and responsive to emerging challenges.

Chapter 4: The Anthropocene Paradigm and Power Politics

Climate change in the Anthropocene is no longer merely an environmental or technical problem; it has become a fundamental challenge to the survival of human societies and the planet. The Anthropocene reframes climate governance as a question of planetary survival, emphasizing the unprecedented scale and speed of human influence on Earth systems. This paradigm shift has profound implications for international relations, diplomacy, and global governance, highlighting the interplay between ecological imperatives and entrenched power structures. While the urgency of the climate crisis demands cooperative action, power politics continue to shape the negotiation of responsibilities, resources, and outcomes. This chapter examines the intersection of the Anthropocene paradigm and power politics, exploring historical responsibility, vulnerability, equity, and the principles that underpin international climate negotiations.

4.1 Historical Responsibility and the North–South Divide

A central feature of power politics in climate governance is the asymmetry of historical responsibility. Industrialized states, particularly those that led global industrialization, have contributed the largest share of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, these states often prioritize economic growth and competitiveness over ambitious mitigation measures. Conversely, many developing countries, though responsible for a small fraction of historical emissions, are disproportionately vulnerable to climate impacts. Rising sea levels, desertification, and extreme weather events threaten livelihoods, infrastructure, and national security, creating an acute sense of urgency for these nations.

The tension between historical responsibility and current vulnerability is institutionalized in international climate frameworks through the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR). This principle recognizes that all nations share a duty to address climate change, but obligations must be differentiated according to historical emissions, economic capacity, and developmental needs. CBDR reflects both ethical considerations and strategic negotiation: industrialized nations are expected to provide financial resources, technology transfer, and capacity-building support to developing states. However, disputes over the scope, adequacy, and enforceability of these obligations illustrate the enduring influence of power politics in shaping climate diplomacy.

4.2 Vulnerability, Equity, and Climate Justice

Vulnerability and equity are critical dimensions of power politics in the Anthropocene. States and communities with limited adaptive capacity face heightened exposure to climate risks, making climate change both a development and security issue. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and least-developed countries (LDCs) have consistently advocated for recognition of their unique vulnerabilities in international negotiations, seeking mechanisms such as climate finance, adaptation support, and compensation for loss and damage.

The discourse of climate justice has emerged as a central framework for addressing these inequities. Climate justice emphasizes fairness in burden-sharing, intergenerational responsibility, and the moral obligation of high-emission states to support those most affected. Negotiations over financial assistance, technology transfer, and adaptation strategies reveal the persistent power asymmetries between developed and developing nations. Industrialized states may resist binding commitments, citing economic constraints, while developing nations insist on accountability and reparation for historical harms. These debates underscore that climate diplomacy in the Anthropocene is as much about justice and fairness as it is about emission reductions or technical solutions.

4.3 Power Dynamics in Climate Negotiations

Power politics continues to shape climate negotiations at multiple levels, influencing both the substance of agreements and the process of diplomacy. In the Anthropocene, climate governance is not only a technical or environmental challenge but a contest over resources, responsibility, and authority. Understanding these dynamics requires an examination of state hierarchies, coalition-building, the role of emerging economies, and the participation of non-state actors in shaping outcomes.

4.3.1 Influence of Industrialized States

Industrialized states historically bear the largest responsibility for cumulative greenhouse gas emissions. Consequently, they occupy a dominant position in climate negotiations, leveraging economic, technological, and political resources to shape agreements in ways that protect their national interests. Their influence manifests in several ways: controlling the negotiation agenda, providing conditional financial assistance, and shaping the technical frameworks of emission reduction mechanisms. For instance, the flexibility provisions in the Kyoto Protocol and the voluntary “Nationally Determined Contributions” under the Paris Agreement reflect compromises designed to accommodate industrialized countries’ economic and political concerns. However, these concessions often generate tension with developing nations, which seek more binding commitments and equitable burden-sharing. The power of industrialized states highlights the persistent North–South asymmetry in climate diplomacy, illustrating how historical responsibility and contemporary influence intersect to shape global governance outcomes.

4.3.2 Role of Emerging Economies

Emerging economies, including China, India, Brazil, and South Africa, occupy a complex position in climate negotiations. These countries are simultaneously major emitters, developing economies, and important players in global economic and political systems. Their strategic interests require balancing developmental priorities with international expectations for mitigation and sustainability. Emerging economies often resist overly restrictive obligations that might constrain industrial growth, while simultaneously emphasizing the need for financial and technological support from industrialized nations. This dual positioning allows them to act as bridge-builders in negotiations, mediating between developed and least-developed countries, while also asserting their own regional and global influence. Their engagement demonstrates that climate diplomacy is not merely a contest between industrialized and developing nations but a dynamic negotiation among multiple actors with shifting capacities and interests.

4.3.3 Coalition-Building and Collective Bargaining

To counterbalance the influence of powerful states, less powerful countries often form coalitions to amplify their voices and negotiate collectively. Notable examples include the G77, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), and the Least Developed Countries (LDC) group. These coalitions play a strategic role in framing negotiation priorities, advocating for climate justice, and demanding accountability for financial assistance, technology transfer, and adaptation support. Coalition-building enhances bargaining power by creating unified positions, pooling technical and diplomatic expertise, and increasing visibility in international forums. However, coalition dynamics are complex, as members may have divergent priorities or domestic constraints, requiring careful negotiation and compromise within the coalition itself. Such strategies illustrate the multi-layered nature of power in climate diplomacy and highlight the importance of collective action for achieving equity in global governance.

4.3.4 Influence of Non-State Actors

The landscape of climate diplomacy has expanded beyond state actors, incorporating cities, corporations, NGOs, and transnational advocacy networks into governance processes. Non-state actors introduce innovation, experimentation, and new mechanisms for mitigation and adaptation. Urban initiatives, such as city-level emission reduction programs, and corporate sustainability commitments, such as renewable energy investments, contribute to a polycentric governance model that complements formal state-led diplomacy.

However, the influence of non-state actors is double-edged. While they enhance governance flexibility and innovation, they may also reinforce existing power hierarchies or create new inequities. For example, corporate-led initiatives may favor profitable markets or high-visibility projects, neglecting marginalized communities or regions most vulnerable to climate impacts. NGOs and advocacy networks may amplify certain voices while marginalizing others, raising questions about legitimacy, accountability, and equitable representation. Navigating this complex web of state and non-state power requires climate diplomats to balance ethical responsibility, strategic compromise, and long-term planetary vision, ensuring that the negotiation process advances both mitigation goals and global justice imperatives.

Chapter 5: Experimentation and Innovation in Governance

As the limitations of traditional state-centric treaties and international agreements become increasingly apparent, climate governance has evolved toward experimentation and innovation. Formal treaties, such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, have advanced global action on climate change but often face constraints including weak enforcement mechanisms, reliance on voluntary commitments, and slow consensus-building processes. In response, cities, corporations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and transnational networks have emerged as critical actors, experimenting with new governance models, policies, and technologies. This chapter explores the diverse forms of experimentation, their contributions to climate governance, and the potential challenges arising from decentralized and multi-actor approaches.

5.1 Urban Climate Governance and City Networks

Cities have become pivotal actors in climate governance, particularly as national governments sometimes struggle to implement ambitious policies. Metropolitan areas like New York, London, and Tokyo have committed to aggressive emission reduction targets, sustainable transport policies, and green infrastructure initiatives. City networks such as the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, and the Global Covenant of Mayors provide platforms for knowledge-sharing, collaborative policy-making, and the dissemination of best practices. These networks facilitate rapid experimentation, enabling cities to pilot innovative solutions such as low-emission zones, renewable energy integration, and urban climate adaptation strategies.

Urban climate governance demonstrates that localized, flexible, and context-specific approaches can complement global agreements. However, city-led initiatives also reveal limitations: while they can achieve substantial emissions reductions locally, their impact on national or global targets may be constrained. Moreover, cities often depend on national governments for regulatory support, funding, and policy alignment, creating potential tensions between local ambition and state-level priorities.

5.2 Corporate Innovation and Voluntary Market Mechanisms

Corporations are increasingly significant actors in climate governance, introducing technological innovation, voluntary carbon markets, and sustainability programs. Companies such as Microsoft, Unilever, and Tesla have committed to carbon neutrality, invested in renewable energy, and developed innovative technologies for energy efficiency, carbon capture, and sustainable production. Voluntary carbon markets allow firms to offset emissions while funding climate projects, demonstrating a market-driven approach to mitigation that complements governmental policies.

Corporate experimentation contributes to climate governance by introducing efficiency, innovation, and resources beyond the reach of public institutions. Yet, these initiatives are not without challenges. Market-based mechanisms may lack transparency, standardized measurement, and rigorous verification, raising questions about their environmental integrity. Additionally, voluntary corporate commitments may prioritize branding and reputation over systemic emissions reduction, highlighting the need for regulatory oversight and alignment with broader climate objectives.

5.3 Role of Non-Governmental Organizations and Transnational Advocacy

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and transnational advocacy networks have also become critical actors in climate governance experimentation. Organizations such as WWF, Greenpeace, and the Climate Action Networkengage in advocacy campaigns, policy research, and public mobilization, pressuring states and corporations to adopt ambitious climate targets. NGOs facilitate multi-actor dialogues, foster innovation in governance strategies, and act as watchdogs to enhance accountability.

These actors contribute to polycentric governance, enabling diverse approaches to mitigation and adaptation across sectors and scales. They also serve as knowledge brokers, connecting scientific research, local experience, and international policy frameworks. However, the involvement of NGOs raises questions about legitimacy and accountability. Their influence may disproportionately reflect the priorities of donors or specific interest groups, rather than democratic consensus, and their fragmented initiatives can create overlaps or inconsistencies with formal governmental policies.

5.4 Challenges of Decentralized and Multi-Actor Governance

While experimentation and innovation expand the toolkit of climate governance, they also introduce significant challenges of fragmentation, coordination, and legitimacy. The proliferation of actors, networks, and initiatives may result in overlapping responsibilities, inconsistent policies, and difficulties in measuring collective progress toward global climate targets. Polycentric governance demands robust coordination mechanisms, data-sharing protocols, and adaptive management strategies to ensure coherence and effectiveness.

Legitimacy is another critical concern. Unlike intergovernmental agreements, decentralized governance mechanisms may not be subject to formal democratic oversight or accountability frameworks. Questions arise regarding who sets priorities, who monitors outcomes, and how stakeholders—particularly marginalized communities—are represented. Addressing these concerns requires integrating experimentation with transparent governance, inclusive decision-making, and alignment with international agreements to ensure that innovation supports global climate goals rather than undermining them.

Chapter 6: Nationalism, Globalism, and Climate Security

Climate change in the Anthropocene not only represents an environmental challenge but also intersects with questions of national identity, global responsibility, and security. The interplay between nationalism and globalism shapes the strategies, priorities, and effectiveness of climate governance. On one hand, national governments often emphasize sovereignty, economic competitiveness, and domestic political agendas. On the other hand, the global nature of climate risks demands cooperative action that transcends borders. This chapter explores how nationalism, globalism, and the securitization of climate issues influence international climate diplomacy and the prospects for achieving long-term planetary survival.

6.1 Nationalism and Domestic Priorities

The resurgence of nationalism in many countries has significant implications for climate governance. Nationalist policies often prioritize short-term domestic economic growth, employment, and energy security over long-term global climate objectives. Governments may resist binding international commitments that could constrain fossil fuel industries, slow industrial development, or incur political costs. Examples include withdrawal or limited participation in global agreements, delayed implementation of emission reduction policies, or prioritization of domestic energy production over international climate cooperation.

Nationalism can also manifest through domestic political rhetoric, emphasizing sovereignty and national interest over collective responsibility. While this approach resonates with electorates concerned with immediate economic and social stability, it undermines cooperative frameworks required to address a global problem like climate change. Consequently, negotiations in forums such as the UNFCCC must navigate tensions between the self-interest of nation-states and the collective imperative of planetary survival.

6.2 Globalism and Transnational Cooperation

In contrast to nationalism, globalism emphasizes interconnectedness and collective responsibility. Climate change is inherently transboundary: greenhouse gas emissions, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events do not respect national borders. Globalism encourages states to adopt policies that recognize interdependence, support climate finance, and facilitate technology transfer to developing nations. Multilateral agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, are products of a globalist framework, aiming to balance flexibility with accountability and shared ambition.

Global cooperation is further reinforced by transnational networks of cities, corporations, NGOs, and international organizations. These actors operationalize globalism by implementing policies, innovations, and advocacy campaigns that extend beyond national jurisdiction. For example, the C40 Cities network demonstrates how cities across continents collaborate to reduce emissions, share best practices, and complement national-level commitments. Globalism emphasizes the ethical dimension of climate action, highlighting that safeguarding the planet is not just an altruistic endeavor but a requirement for survival in an interconnected world.

6.3 Climate Change as a National Security Threat

Climate change has been increasingly framed as a national and international security issue, adding urgency to diplomatic and policy agendas. Rising temperatures, resource scarcity, and extreme weather events can exacerbate conflicts over water, food, and energy. Vulnerable regions may experience mass displacement, migration, and social unrest, creating potential instability that transcends borders. States are increasingly recognizing that climate risks threaten military readiness, infrastructure, and economic stability.

The securitization of climate change has advantages: it elevates climate action on political agendas, attracts funding, and mobilizes strategic planning. Militaries and defense institutions are now incorporating climate projections into risk assessments, disaster preparedness, and resource allocation. However, framing climate change primarily as a security issue also carries risks. It may militarize discourse, prioritize short-term risk management over sustainable, cooperative solutions, and sideline marginalized communities whose interests may not align with national security priorities. Balancing security concerns with ethical, long-term climate governance is thus a critical challenge for global diplomacy.

6.4 Reconciling Nationalism, Globalism, and Cooperative Action

The tension between nationalism and globalism shapes the trajectory of climate diplomacy. Effective governance requires integrating national interests with global imperatives, fostering policies that meet domestic needs while contributing to planetary survival. This balance can be achieved through mechanisms such as conditional commitments, climate finance, technology transfer, and incentivizing sustainable development strategies that align national priorities with global goals.

Additionally, polycentric governance—encompassing state, city, corporate, and NGO initiatives—offers a framework to reconcile divergent interests. By creating overlapping layers of cooperation, states can pursue domestic goals without undermining global objectives. Diplomats must also emphasize ethical responsibility and intergenerational equity, framing climate action not merely as a national or economic issue but as a shared human obligation. Reconciling nationalism and globalism is therefore not just a strategic necessity but a moral imperative in the Anthropocene.

Chapter 7: The Paris Agreement and Beyond

The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), marked a turning point in global climate diplomacy. Unlike earlier treaties such as the Kyoto Protocol, which imposed binding targets primarily on developed countries, the Paris framework introduced a “pledge and review” system that emphasizes inclusivity, transparency, and flexibility. This innovative approach sought to reconcile the diverse capacities, responsibilities, and priorities of states while fostering near-universal participation. However, the Agreement also reflects the ongoing challenges of climate diplomacy in the Anthropocene, including questions of ambition, compliance, and the integration of non-state actors. This chapter examines the architecture, achievements, limitations, and future trajectories of the Paris Agreement in global climate governance.

7.1 The Architecture of the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement introduced a bottom-up approach to climate governance, requiring states to submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that reflect their domestic capacities, priorities, and development goals. Unlike the Kyoto Protocol’s top-down targets, this system allows for flexibility and encourages broader participation, enabling both developed and developing countries to engage in the mitigation process.

Key features of the Paris framework include:

- Regular reporting and review mechanisms, ensuring transparency and accountability.

- Global stocktake every five years, assessing collective progress and encouraging enhancement of NDCs.

- Climate finance commitments, whereby developed countries support developing nations through funding, technology transfer, and capacity-building initiatives.

By accommodating diverse national circumstances and emphasizing iterative improvement, the Paris Agreement reflects an adaptive governance model designed for the complexity of the Anthropocene. Its architecture balances sovereignty and cooperation, seeking to align global climate objectives with domestic realities.

7.2 Achievements and Strengths

The Paris Agreement represents several notable achievements in international climate diplomacy. First, it achieved near-universal participation, with 196 parties adopting the framework, reflecting unprecedented global consensus on the urgency of climate action. Second, it has institutionalized transparent reporting mechanisms, enhancing accountability and allowing states and non-state actors to track progress.

Furthermore, the Agreement has stimulated innovative climate action beyond state commitments. Cities, corporations, NGOs, and transnational networks have aligned initiatives with national NDCs, accelerating mitigation and adaptation efforts. Examples include corporate net-zero pledges, city-level renewable energy programs, and collaborative research initiatives for climate-resilient technologies. The Paris Agreement thus functions not only as a diplomatic instrument but also as a catalyst for polycentric governance, where multiple actors contribute to achieving global targets.

7.3 Limitations and Challenges

Despite its achievements, the Paris framework faces significant limitations. The reliance on voluntary commitments raises concerns about ambition and compliance, as there are no legally binding enforcement mechanisms to ensure states meet or exceed their NDCs. Many NDCs currently fall short of the emission reductions required to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, underscoring a persistent ambition gap.

Equity and finance remain contentious issues. Developing nations continue to demand greater support from industrialized countries, citing historical responsibility and vulnerability to climate impacts. Delays or inadequacies in climate finance, coupled with differences in technological capacity, create friction in negotiations and challenge the notion of shared but differentiated responsibilities. Moreover, the Paris framework relies heavily on good faith and political will, which can fluctuate with changes in national leadership, economic crises, or competing domestic priorities.

7.4 The Road Beyond Paris

Looking beyond the Paris Agreement, climate governance must address both implementation and enhancement. Strengthening ambition requires:

- Periodic review and upward adjustment of NDCs, incentivized through international peer pressure, transparency mechanisms, and cooperative initiatives.

- Integration of non-state actors in monitoring, innovation, and accountability to reinforce state commitments and extend governance capacity.

- Adaptive governance strategies, capable of responding to new scientific knowledge, technological developments, and emerging climate risks.

Additionally, the future of climate diplomacy will likely involve linking mitigation and adaptation efforts with broader socio-economic objectives, such as sustainable development, energy transition, and social equity. The Paris Agreement provides a framework, but success depends not only on negotiation outcomes but also on the willingness of states, cities, corporations, and civil society to honor commitments, strengthen them over time, and collaborate across scales. The Anthropocene demands governance that is iterative, inclusive, and responsive to planetary boundaries, moving beyond treaties as static instruments toward dynamic, multi-actor processes.

Chapter 8: Negotiating Survival in the Anthropocene

Climate diplomacy in the Anthropocene extends far beyond conventional environmental negotiation. The epoch underscores that human activity has become a dominant geological force, creating systemic risks that threaten the stability of Earth’s life-support systems. In this context, diplomacy is no longer solely about managing conflicts of interest between states; it is about negotiating strategies for collective survival. Achieving this requires governance systems that are inclusive, adaptive, and resilient, capable of addressing both immediate crises and long-term planetary challenges. This chapter examines the conceptual, political, and practical dimensions of negotiating survival in the Anthropocene, highlighting the roles of sovereignty, cooperation, and planetary stewardship.

8.1 Rethinking Sovereignty and Global Interdependence

Traditional concepts of sovereignty are increasingly challenged in the Anthropocene. Climate risks—ranging from rising sea levels and extreme weather events to widespread biodiversity loss—transcend national borders, creating interdependencies among states that cannot be managed unilaterally. Consequently, negotiating survival requires a redefinition of sovereignty, moving from a narrow focus on territorial control to a broader understanding of shared responsibility.

States must recognize that national interests are inextricably linked to global well-being. For example, sea-level rise in low-lying nations can trigger migration and economic disruptions far beyond national borders, affecting regional and global stability. Sovereign decision-making must therefore incorporate considerations of collective risk, ethical responsibility, and planetary boundaries. Climate diplomacy in this context becomes a platform for balancing domestic imperatives with global interdependence, requiring innovative strategies to align state policies with planetary survival goals.

8.2 Adaptive Governance and Multi-Actor Collaboration

Negotiating survival in the Anthropocene necessitates adaptive governance, which is flexible, iterative, and capable of responding to evolving scientific, technological, and social insights. Traditional treaty-based frameworks are insufficient to address the scale, complexity, and uncertainty of climate risks. Adaptive governance emphasizes learning from experimentation, incorporating feedback loops, and fostering policy resilience in the face of unexpected shocks.

In practice, this approach involves multi-actor collaboration. States, cities, corporations, NGOs, and international institutions must work together to implement mitigation and adaptation strategies. Networks such as C40 Cities, the Global Covenant of Mayors, and transnational corporate alliances illustrate how decentralized, polycentric governance can complement formal agreements. These actors not only enhance capacity and innovation but also help bridge gaps in implementation, monitoring, and accountability. The challenge lies in coordinating diverse actors, ensuring equitable participation, and maintaining coherence with global climate objectives.

8.3 Planetary Stewardship and Ethical Imperatives

At the philosophical and normative level, negotiating survival in the Anthropocene calls for a paradigm shift from interest-based diplomacy to planetary stewardship. States and societies must recognize that the long-term stability of human civilization is contingent upon the health of Earth’s ecological systems. This perspective reframes climate diplomacy as an ethical project, emphasizing intergenerational responsibility, justice, and equity.

Planetary stewardship entails aligning governance with the resilience of ecosystems, protecting biodiversity, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and safeguarding critical resources such as water, soil, and forests. It also requires addressing social inequalities that exacerbate vulnerability to climate impacts. By embedding ethics, science, and policy within a common framework, climate diplomacy can transcend traditional divides, creating opportunities for cooperation that reflect shared survival imperatives. In this sense, survival negotiation becomes not just a technical or political exercise but a moral commitment to safeguarding the planetary commons for present and future generations.

Conclusion

Climate diplomacy and global governance in the Anthropocene represent a critical frontier in international relations, challenging the assumptions, frameworks, and practices that have long underpinned the global order. This dissertation has examined how climate change—an existential, transboundary, and systemic threat—transforms diplomacy from a tool of negotiation over national interest into a mechanism for negotiating human survival and planetary stewardship. Traditional models of international relations, centered on sovereignty, power competition, and state-centric security, are insufficient to address the complex dynamics of the Anthropocene, where ecological thresholds, global interdependence, and ethical responsibility define the parameters of effective governance.

The analysis has highlighted that climate diplomacy has evolved in response to both failures and innovations. Institutional mechanisms, such as the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, illustrate the potential for multilateral cooperation while also revealing limitations related to enforcement, ambition, and equity. Polycentric governance approaches—comprising cities, corporations, NGOs, and transnational networks—demonstrate innovative pathways for implementation, offering flexibility, experimentation, and cross-sectoral engagement. Yet these developments also raise questions about legitimacy, accountability, and coherence, underscoring the need for hybrid governance systems that integrate state and non-state actors in ways that are both effective and ethically grounded.

A critical finding of this study is the persistent tension between power politics and climate justice. Industrialized nations, historically responsible for the majority of emissions, continue to wield disproportionate influence, while developing and least-developed countries bear the greatest vulnerability. The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) embodies this tension, reflecting ongoing debates over historical responsibility, financial support, and equitable burden-sharing. Negotiating survival in the Anthropocene therefore requires diplomacy that moves beyond transactional, interest-based bargaining toward strategies informed by justice, cooperation, and long-term planetary stewardship.

The Anthropocene also demands a rethinking of the very concepts of sovereignty, security, and responsibility. Climate change exemplifies a boundary-crossing threat that challenges the traditional Westphalian model of state-centric authority. Nationalism and globalism intersect in ways that complicate collective action: states may prioritize domestic interests while recognizing the necessity of transnational cooperation. The securitization of climate issues underscores the urgency of action but must be balanced with ethical, inclusive, and sustainable governance strategies. Multi-actor collaboration, adaptive governance, and ethical stewardship emerge as indispensable tools for negotiating climate risks in a globally interdependent system.

Finally, this dissertation emphasizes that the future of climate diplomacy lies in reframing international relations as a collective enterprise of planetary survival. This entails a paradigm shift from viewing diplomacy as a mechanism for relative advantage toward seeing it as a practice of shared responsibility—one in which mitigation, adaptation, equity, and intergenerational justice are central objectives. The Anthropocene compels policymakers, diplomats, and scholars alike to embrace innovative governance architectures, integrate non-state actors, and foreground ethical imperatives in decision-making. In essence, climate diplomacy must become a vehicle for ensuring that humanity not only survives but thrives within the ecological limits of the planet.

In conclusion, the Anthropocene challenges the international community to reimagine governance, cooperation, and diplomacy. It is a call to recognize that climate action is inseparable from justice, equity, and human security, and that the effectiveness of global governance depends on the ability of states, institutions, and societies to negotiate not merely interests, but survival itself. The findings of this dissertation contribute to a broader understanding of how international relations theory, diplomacy, and global governance can evolve to meet the extraordinary challenges of the 21st century, providing both analytical insights and practical guidance for policymakers engaged in the urgent task of securing a sustainable and resilient future.

References

- Bodansky, D. (2016). The Art and Craft of International Environmental Law. Harvard University Press.

- Bulkeley, H., Andonova, L. B., Betsill, M. M., Compagnon, D., Hale, T., Hoffmann, M., … & VanDeveer, S. D. (2014). Transnational Climate Change Governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125.

- Gupta, J. (2014). The History of Global Climate Governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Hale, T. (2020). Catalytic cooperation. Global Environmental Politics, 20(4), 73–98.

- Held, D., Fane-Hervey, A., & Theros, M. (2011). The governance of climate change in developing countries: International cooperation and the transition to sustainable development. Global Policy, 2(1), 65–75.

- Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. G. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspectives on Politics, 9(1), 7–23.

- Klein, N. (2014). This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. Simon & Schuster.

- Latour, B. (2017). Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Polity Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557.

- Roberts, J. T., & Parks, B. C. (2007). A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy. MIT Press.

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., … & Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472–475.

- Sachs, J. D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

- Steffen, W., Crutzen, P. J., & McNeill, J. R. (2007). The Anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(8), 614–621.

- UNFCCC. (2015). The Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

- Zürn, M. (2018). A Theory of Global Governance: Authority, Legitimacy, and Contestation. Oxford University Press.